The final pillar of Globalization is the fast expansion of

the free trade liberalization and free labor mobility. Basically, the free

trade liberalization is divided into two mechanisms of negotiation such as

custom union and free trade areas schemes. For this reason, many academics

present strong claims in favor of free trade areas breaks down economic

nationalism and increases awareness of economic interdependence; that it makes

negotiation easier by reducing the number of international trade players; and that

it encourages the codification and formalization of rules and regulations

affecting international trade, making them more transparent and less capricious

and discretionary, if not always more liberal. Further, this paper argues in

favor of the idea of free trade brings more benefits to international trade

than regionalism. We asserts that if the number of trade blocs increases, then

trade welfare in the world trade will decrease. Moreover, two categories of

trade blocs are applied in this research (Ruiz Estrada, 2016). These two

categories of trade blocs, there are closed trade blocs and open trade blocs.

Closed trade blocs is based on the import-substitution

industrialization strategy under the infant industry argument. The

import-substitution industrialization strategy uses a common import tariff that

is a form of government intervention to protect the domestic industries and to

create a large market (Balassa, 1985). Closed trade blocs has observed a series

of phases in the process towards the creation of a single trading bloc. These

six phases are first phase is the preferential trade arrangements. Second

phase, the free trade area will eliminate internal tariff and non-tariff

barriers but not harmonize external barriers. Third phase is the Customs union,

which is trying to remove internal barriers and establish a common external

tariff. Fourth phase is common markets, which is formed by a customs unions and

where free mobility of labor and capital are eliminated. The fifth phase is to

establish a common currency and common economic policies based on an economic

and monetary union. Finally, nations can form a single state in a confederation

according to Lawrence (1996).

Open trade blocs were developed and promoted at the end of

the 1990’s. Based on trade liberalization or open market, it uses the

export-led oriented or outward oriented model. Contrary to closed trade blocs,

open trade blocs seek to eliminate all trade barriers and non-trade barriers in

the same region based on a minimal government intervention which is applied to

protect domestic industries from foreign competition. The open trade blocs as a

negotiating framework consistent with and complementary to GATT/WTO. But, as

they point out, ‘openness’ carries at least two different meanings: openness in

terms of non-exclusivity of membership; openness in terms of contributing

economically to the process of global liberalization than detracting from it

through discrimination. It is difficult to implement open trade blocs between

developing countries and least developed countries. This is because these

countries lack the same kind of economic, political,

social and technological conditions respectively. However,

it is inappropriate to argue that open trade blocs is the ideal scheme to

integrate middle income countries with low income countries in order to compete

in world trade (Ruiz Estrada, 2016).

In trade liberalization there is not only free mobility of

goods and services, but also the fast mobility of labor domestically and

internationally. In fact, the domestic and international labor mobility plays

an important role in the globalization process around the world. The demand and

supply of low and high qualified labor becomes more significant and volatile

through globalization process.

In the analysis of labor mobility in the

globalization process, we like to introduce a new concept is entitled “the post-modern-labor

mobility”. The post-modern-labor mobility is based on the opportunities of

better jobs, better knowledge and skills, high wages, social security, low

taxation, diversify public services under new migration and immigration schemes

for any worker. According to this research the immigration among different

regions has expanded exponentially in the past 30 years, especially in the

period 2000-2020. The growth rate of immigrats during this period was from 25%

to 35% worldwide. According to our indicator the immigration growth rate (ΔÐ)

results. During this period, the highest ΔÐ at the intra-regional level took

place in European Union –EU-, where the rate increased from 11% in the 2000 to

35% in the 2020. North America Free Trade Area –NAFTA- is second after EU with

its ΔÐ growing from 10% in the 2000 to 30% in the 2020. In this case, the bulk

of the ΔÐ originated from immigration from Mexico and Canada to U.S. In the

2020 Latin America witnessed a high ΔÐ of 45% where the ilegal and legal

immigration flows were into U.S. Asia had an ΔÐ of 25% in the same period. In

this case the immigration flows work oriented to Australia, China, U.S. and

Europe in order of (immensity) of immigration. For Africa (Sahara north part)

to Europe (Spain and France) the ΔÐ for the same period was 15%, where the

destination of immigration was Europe. Unlike EU and NAFTA, the orientation of

immigration in Latin America (LA), Asia and Africa is not regional but

worldwide (OECD, 2020).

From the above, it is clear that the trend of immigration in

LA, Africa and Asia is different from that of E.U. and NAFTA. Also the region

with the highest ΔÐ around the world is Latin America (ΔÐ of 35%), follow by

Asia (ΔÐ of 20%) Relating these observations to Globalization, could be seen that

in no limitation to mobility of goods and services, foreign direct investment

(FDI), and labor mobility around the world. The high ΔÐ in Latin America (LA),

Asia and Africa is due to high levels of unemployment, constant growth of

inflation rate, constant depreciation of exchange rate and slow per-capita

growth (resulting from imbalance distribution of wealth). All these negative

factors can be considered the basic reasons these regions (LA, Asia and Africa)

are unable to retain their full domestic labor in these regions. In other

words, the above mentioned factors were the underlying reasons for limited

domestic

labor demand in LA, Asia and Africa. These factors jointly

result in small output production (GDP) in these three regions. Moreover, the

small output production (GDP) in these three regions have been based on limited

basket of agriculture products (coffee, fruits, vegetables and raw materials)

and manufacturing products (clutches and electro-domestics) with low added

value that fetch low prices in the international market that constitutes the

push factors for immigrations out of the regions. Additionally, LA, Asia and

Africa a phase with several common problems in their domestic labor supply

structures: basically, only a small percentage of the population has the

opportunity to obtain a tertiary education, and even this small percentage of

population cannot be absorbed completely by the domestic productive structure

for employment. This surplus in labor supply pushes down the wages for all. In

the short term this factor generates low productivity and non-efficient

allocation of resources (financial resources, human resources, and natural

resources) and production factors (labor –L-, capital –K-) in the domestic

productive structure. The overall scenario is that Developing countries and

LDC’s in LA, Asia and Africa cannot absorb their own surplus domestic labor. In

the long run this surplus domestic labor start to search for new opportunities

in large countries or regions with high output of production (GDP) and where

they are offered high income, social security, working environment, jobs

prospects, and jobs security.

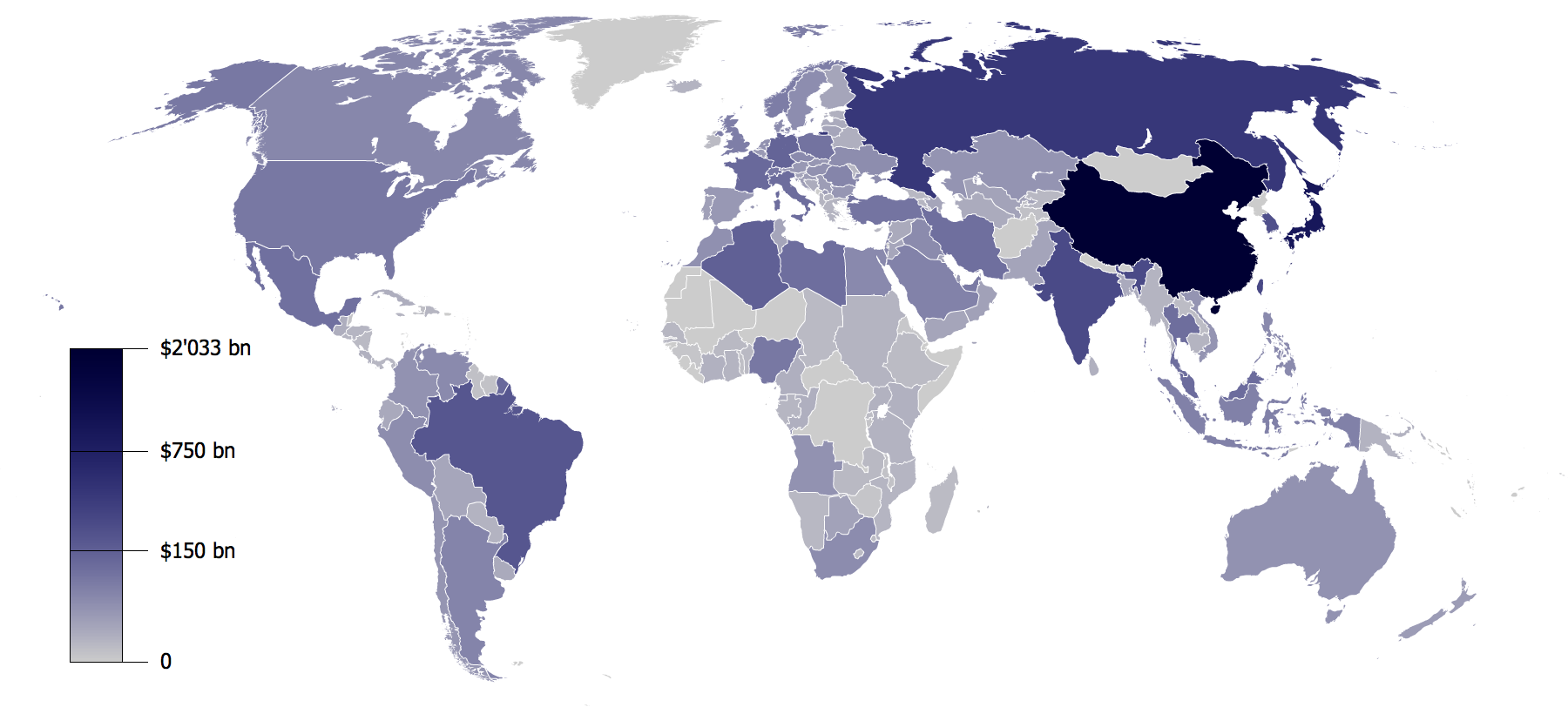

Finally, we try to figurate the impact of Wuhan-COVID-19 in

the international trading and labor mobility in the case of China and the rest

of the world. We assume that any massive contagious epidemic diseases such as

Wuhan-COVID-19 can affect the exports of China worldwide severaly and

unemployment (jobs diversion). Subsenquently, the drops of China exports can

generate a large imported inflation to the rest of the world respectively. At

the same time, we assume also that exist a high possibility that any imported

product from China can carry the Wuhan-COVID-19 and generate a considerable

increment in the number of Wuhan-COVID-19 infected cases and deaths.

Additionally, we can perceive also that the Wuhan-COVID-19 can generate symptom

of psychosis from a large number of worldwide buyers to getting infected by the

Wuhan-COVID-19. Hence, the free trade liberalization is going to experience a deep

transformation after Wuhan-COVID-19 with new challenges under new trade

regulations and non-tariff barriers such as heavy sanitrary standards and large

physiosanitary controls to avoid possible increment of Wuhan-COVID-19 infected

cases globally. On the other hand, we can assume that the Wuhan-COVID-19 can

stop the domestic, regional, and global labor mobility in China for the long

run. This is possible to observed in the case of Wuhan, China until now. The

quarantine from Wuhan-COVID-19 is blocking a massive number of workers to

return its jobs in another provinces of China. The negative impact of

Wuhan-COVID-19 can stop easily the intra-regional-workers mobility under

unfixed period of time. At the same time, the same labor inmobility can

generate a massive

unemployment under different prefectures, cities, and

regions of China dramatically. We can confirm that the level of unemployment in

China is directly connected to the period of time that the Wuhan-COVID-19

continues active. In the case of Wuhan-COVID-19 can generate a possible

unemployment rate (2020-2021) between 6% and 8% in the short run according to

our preliminary results and calculations in research papers done before.